Opinion

My Climate Journey: Rebuilding Our Systems

I had to present my climate journey to my colleagues, and I found the experience illuminating. Maybe all of you new readers who are not my dad will too!

I’m dazzled by young people who are so purposefully working to halt climate catastrophe RIGHT NOW. I wish I could say I came to climate as a teen, but my journey to climate was circuitous, punctuated by dance breaks, snack breaks, and general indifference. I was a climate late bloomer.

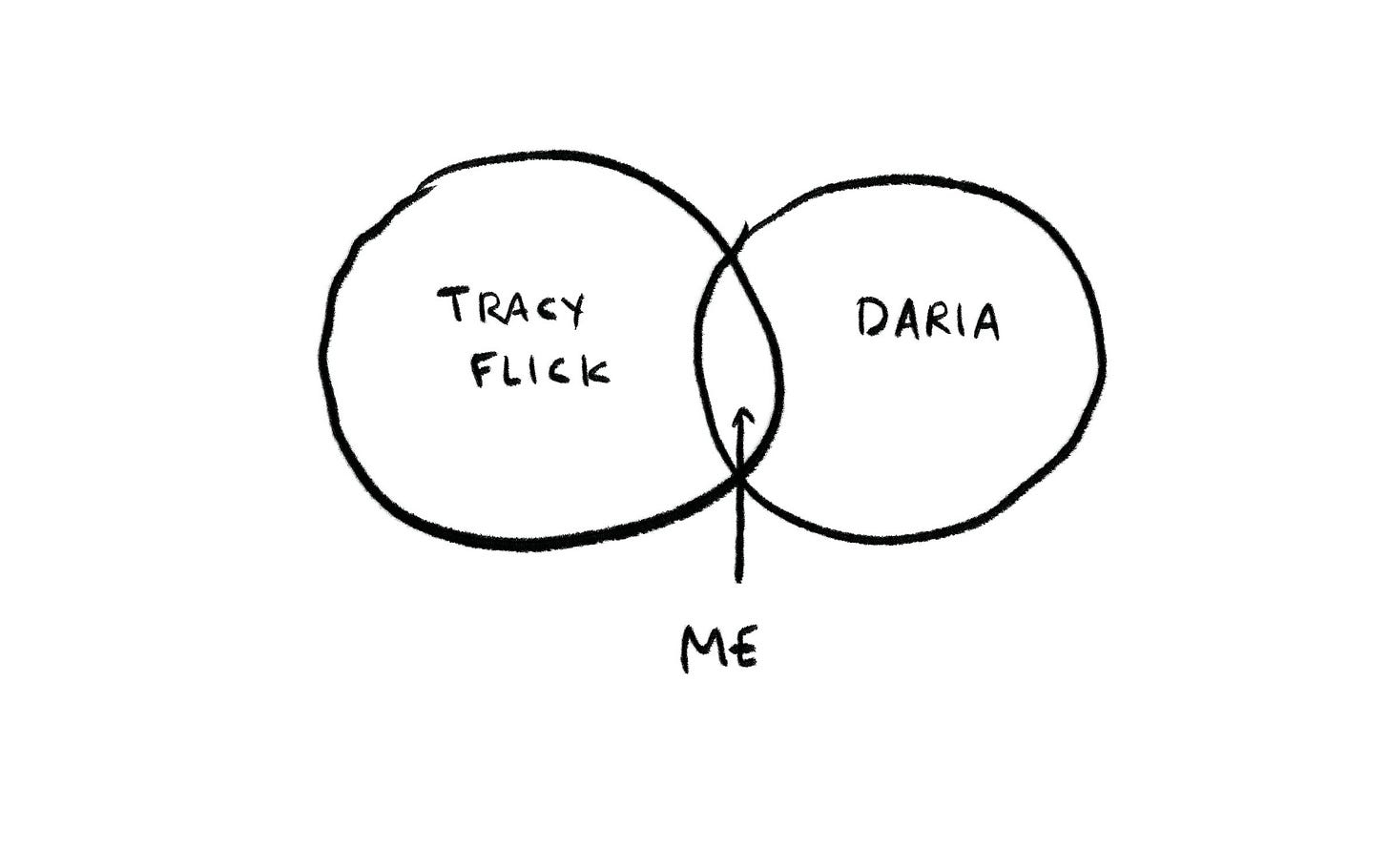

Growing up, I was a “keener” and I did all the things, but mostly because you were supposed to do all the things. I was President of Everything (according to my dad), not because I felt compelled to fix the world, but mostly because I like to be busy and cross things off my to-do lists. I was also a rootless cosmopolitan with no skin in the game, no allegiances to anything except maintaining a snarky, disaffected cool.

I got into film school and thought I would make stories about the human condition or other admirably pretentious things.

But after my first year of university, I contracted a bacterial infection in Egypt and wound up in the hospital in Israel, reading my cousin Foofie’s (not his real name) entire Calvin and Hobbes collection. When I finally got back to film school, I felt (and looked) different. It dawned on me that I had no ideas. No stories to tell. Why was I wasting my program’s money, burning up expensive film on silly bagatelles?

I quit film school and decided to finish university abroad. I ended up living in London and Israel for a while, then moving to Montreal and New York City. I’d like to say I developed a deep climate consciousness at this point. But … nope. I made mumblecore movies and went to Balkan Music Camp and danced a lot, and I thought politics was the purview of deeply boring people, not weird artist gals who were better suited to making guerrilla animations in the park.

But at the same time, something vaguely resembling a political conscience was beginning to seep in. It had a little to do with waste, which I’ve always hated, a hatred I ascribe to growing up in a deeply superficial, have–have not place.

As a sleep-away camp counselor in the beautiful Blue Ridge Mountains, I’d tried to swallow my horror when I saw that the camp used disposable paper plates at every meal, for 900 campers and staff. Three times a day. Plus snacks. I broached the issue with the camp director, who made excuses about water and infrastructure. Nascent activist conscience. Maybe?

But I was becoming a journalist. And journalists didn’t sully their work with pesky little opinions. My job was to observe, not to act. I could fall in love with the lovably egg-headed while at the Liberal party convention, but would never say as much because … objectivity!

At the same time, I was changing. Despite a vehement No New Friends policy, I became buds with someone outside my circle of detached, witty chroniclers. She was interested in climate and caring about things. I finally read some of the formative climate and conservation books I’d always been meaning to get around to, like Silent Spring and A Sand County Almanac.

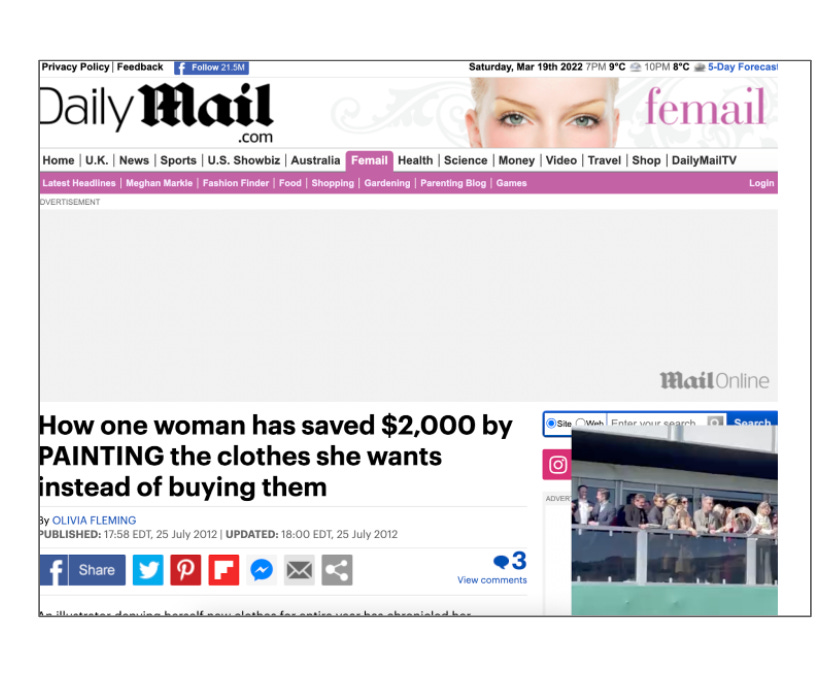

And I was growing increasingly appalled by the pace of waste around me. If you’re roughly my age, you grew up alongside fast fashion and could therefore track how the Gap went from refreshing its clothes every month or so to a world where Zara had new clothes daily. You could see this warp-speed consumerism ramp up everywhere. People were buying more stuff at such a clip that it leapfrogged “worrisome” and went straight to “alarming.” This was not going to be sustainable.

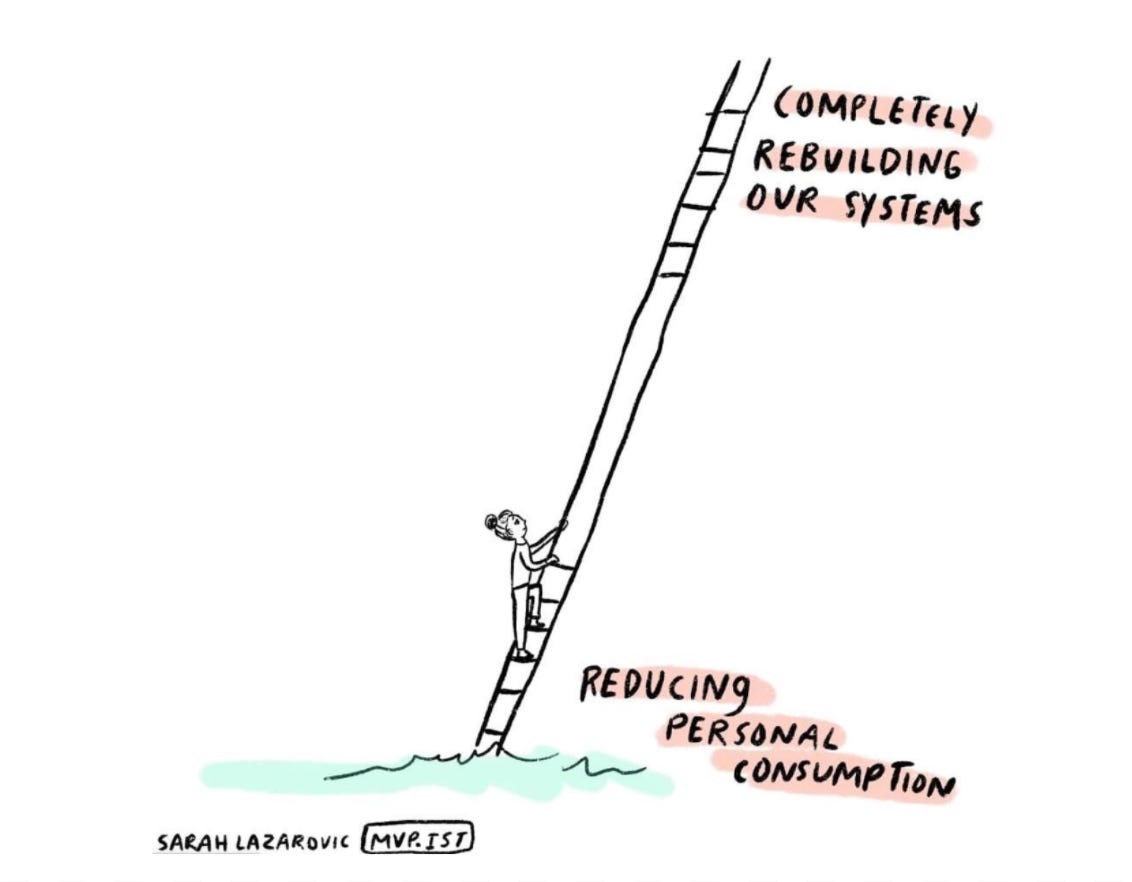

So I did art projects about this (not shopping for a year at a time, painting the things I would have otherwise bought) and eventually wrote a book about this. But it was a very light entry point to climate, more about personal consumption than any of the bigger issues.

I was also going much DEEPER on climate science, and not finding anything good. When my daughter was born in 2010, it all hit in a very bad place. The absolutely delirious joy was coupled with this completely destabilizing sadness that I had never encountered before, that my perfect cherub would inhabit this dying, diminished world. Reader, this was undiagnosed postpartum depression. And postpartum does not mix well with dense tracts about impending sea-level rise.

I would wallow in the science, and it would send me down these horrible paths. It was the precursor to deep adaptation doomer garbage, perpetuated by those I will not deign to mention now. But it wasn’t labeled as such then.

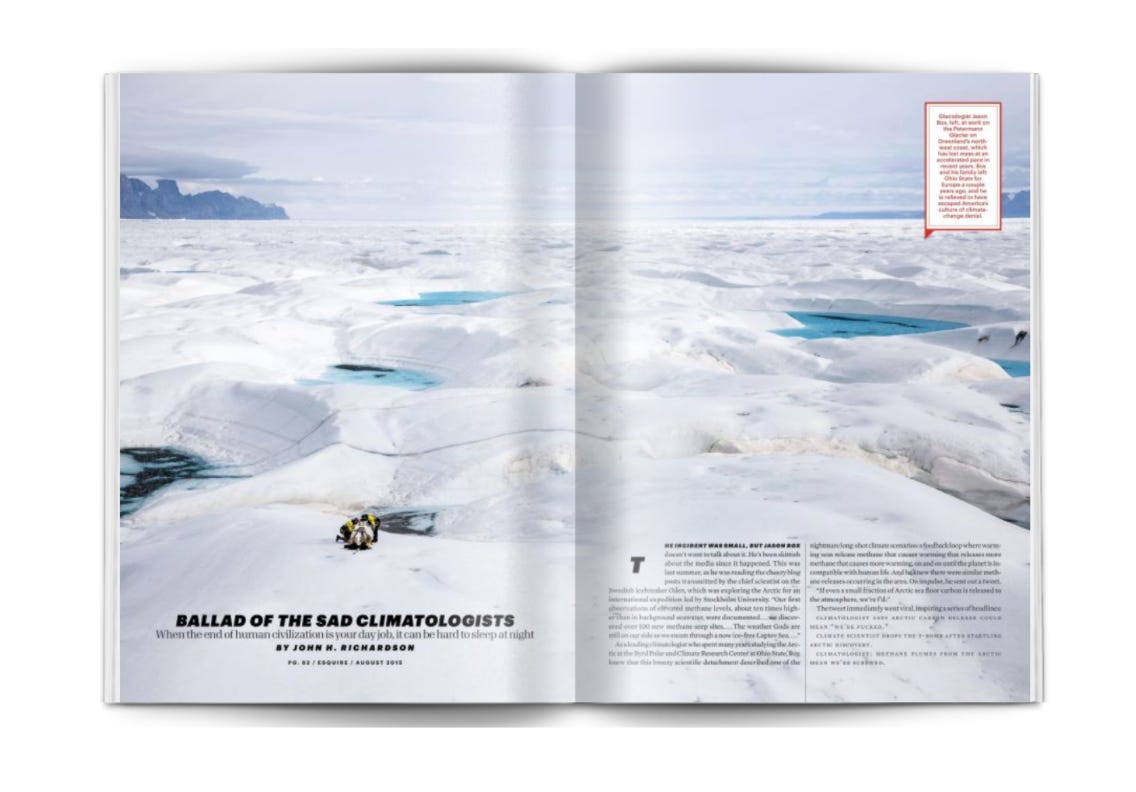

This Esquire story (why do I read Esquire? I don’t know. My dad subscribed to it growing up) didn’t come out until 2015, but really hits at doomer malaise. I flipped the title around in my mind ALL THE TIME: “Ballad of the Sad Climatologists.”

I was just ahead of the eco-grief curve, because I am nothing if not on trend. And resources were hard to come by then.

I was plagued by thoughts of sea-level rise and went deep on the porousness of the limestone bed on which most of South Florida sits. It’s not that the oceans will encroach upon the shores, but that the seawater will seep up through the groundwater.

It cut me deeply, because even though Florida is the worst place in the world, I love it. I was experiencing solastalgia, a beautiful term coined by Glenn Albrecht, an Australian academic, to capture the melancholy and distress one feels at seeing their landscape changed by climate.

I got through it (mostly thanks to my husband making sure I unfollowed all the sea-level scientists). And in some ways, it was good to have experienced this grief so early, because I’ve had a long time to process it and think about how we’ll deal with the juggernaut of humanity that will experience eco-anxiety in the coming years. I’m ready to help.

The experience also finally made me realize I NEEDED TO WORK ON CLIMATE FULL-TIME. I was in the writers room on a kids show, and it was just loud comedians throwing jokes around, trying to outwit each other. I stared at the lead jokester and a profound feeling of NOPE washed over me. I didn’t want to make silly things, though I’m grateful people do. I wanted to be able to say I gave climate everything.

But when I started tentatively stepping into the world of climate communications, it galled me. These words and things were not going to help anything.

Luckily, I met my friend Jode, of the David Suzuki Foundation. We had the same ideas about climate—you have to make it fun, and you have to make it about community. (Read my comic about community?) He basically hired me to do all the funnest, coolest campaigns, activations, and fundraisers. And as the sousaphone echoed loudly through our park pizza party, I began to see that I would find a way.

Which was good, because I was becoming increasingly disenchanted with the “stop shopping” narrative that most people knew me for.

I kept seeing women internalize the guilt of consumption, which really is not theirs to bear. I would watch these wonderful women go deep on zero waste. Which is beautiful, but not a means to solving the wicked problems we face. It felt like the best minds of my sustainable generation were spending their days making lavender soap detergent. I called it Mason Jar Activism. (I love Mason jars.) And while there’s nothing wrong with reducing household waste as a gateway to more significant action, getting stuck in homemade-soap land is not helpful.

I also didn’t like heaping more climate burden onto consumers to deal with what are essentially global, structural problems. Which is why I’m big on carbon labeling and behavioral science—make it easy for people to default to the right choices.

I began to think about how I could take these decision points upstream to alleviate consumer burden. I went back to school to study environmental policy.

Increasingly, I realized that we needed stronger policy to move the dial. In some ways, I’m policy agnostic given the very real climate deadlines we face. I think the key is whichever good policy can be most expediently effected, because we really don’t have time.

In Canada, although flexible regulations might have made a tiny bit more sense, carbon pricing had a foothold, and the data around public support for it was absolutely compelling, so I went to work on it. Helping get $170 a ton in place and improving public awareness of our flagship climate policy made me realize how quickly things can change. Two officials tweak one line on a document and millions of megatonnes of emissions are eradicated in an instant. (If there’s good accountability.)

I was pleased that we got carbon pricing in, but the other piece I was always grappling with was WHAT CAN PEOPLE DO?

I’m so tired of the “vote … and nothing else” narrative. People can do so much more, and they need to be given strong and meaningful things to do. And I absolutely hate the false binary of individual versus systemic action. We have this whole army of concerned climateers screaming “Put me in, coach!” and we are giving them nothing.

Which is how I came to electrification. There are indeed hugely significant things people can do in their homes, businesses, schools, and communities to crush carbon emissions.

As a climate communicator, I am always interested in where we match awareness to action, and right now, helping people become aware of electrification is an absolute no-brainer: We’ve got to get off fossil fuels, we’ve got to get fossil fuels out of our lives.

Electrification also maps to my behavioral science background: There’s a ton of sludge and friction right now—but the key actions are one-and-done—swap out your furnace, change your car. We need to default to zero-carbon.

In the end, I’m a deeply optimistic person, because there’s no other kind to be. We’re alive to do everything we can to keep warming at bay. We’re alive to take personal action, lobby for structural change, advocate for a transition, and build resilient communities. A climate journey is an ongoing, ever-evolving, deeply rewarding thing. And I’m grateful to be on one. Hope you are too!

This Week

What’s your story? Let me know!

People Dancing

How cute is ?

Thanks so much for reading. Always let me know how to make this newsletter better! Hope you are safe and healthy and rested and energized, and enjoying whatever journey you are on,

Sarah

P.S. This is my newsletter for the week of April 15, 2022, published in partnership with ´óĎó´«Ă˝ Media. You can sign up to get Minimum Viable Planet newsletter emailed directly to you at .

|

Sarah Lazarovic

is an award-winning artist, creative director, freelance animator and filmmaker, and journalist, covering news and cultural events in comic form. She is the author of A Bunch of Pretty Things I Did Not Buy.

|